Cities need parks.

The more densely packed the center city, the more necessary are some oases of green. Urban parks are called the city’s lungs, the gardens of the poor. They provide space for refreshment of the spirit and an egalitarian gathering place for human connection.

Milwaukee County is known around the country for its green necklace of parks, the larger ones located generally along the city’s three main rivers and their tributary creeks, or else facing our great lake. Depending on how you count, there are over 150 parcels of green space of various sizes in the county today under government ownership and supervision.

But it was not always so in Milwaukee’s first half-century. Tourist and visitor guidebooks in the 1880s apologized that Milwaukee lagged other great cities of America in its development of public parks. The only public park of any size during those years was Juneau Park on the lakefront. The city acquired the land in 1870, and then soon thereafter pushed its boundaries up to Juneau Ave. by another parcel acquisition and demolition of homes and demapping of Juneau Place, a short lakefront street of several blocks’ length. Horace Cleveland did the design and also arranged to stabilize the shoreline.

A parks commission was finally authorized, led by Christian Wahl. His team hired Frederick Law Olmstead, designer of Central Park in Manhattan, in 1889, and the city began land acquisition in earnest the following year, acquiring the land for Lake Park, Riverside Park, and Washington Park on the west side. Olmstead also planned Newberry Blvd. as a grand link between Lake and Riverside Parks. Lake’s development was first — each year added new reshaping of the terrain to take advantage of its views and topography. The pavilion (now the Lake Park Bistro) was added in 1903 and the grand staircase down to the lakefront in 1908. But it was not until the 1920s and the work of Charles Whitnall that today’s huge network of county parks was acquired and developed.

Milwaukee in the 19th century was one of the most tightly packed urban centers in the country, by some reckoning second in density only to Manhattan. But Milwaukee did not lack urban green spaces in the 19th century—it’s just that the spaces were privately owned and managed. Of all Milwaukee’s ethic groups, the Germans most valued the park concept. They were big into physical fitness and sponsored a half-dozen Turnhalles or exercise clubs; they adored musical performances and singing, sponsoring at least four large buildings in town as headquarters for their various singing clubs; they loved to drink beer in picnic settings; they loved to dance, and they loved good food. Almost all of the private parks were run by Germans.

From the 1850s to the 1890s the private parks were heavily patronized. But in the end four things did them in: 1) competition from the city’s public parks after the turn of the century; 2) World War I’s shaming of all things German; 3) pressure for subdividing the large acreage into residential lots for Milwaukee’s rapidly growing population; 4) The relentless opposition to saloons by the growing numbers of temperance activists, which culminated in national Prohibition in 1919.

There were a dozen or two small pocket parks scattered around the city, such as the half-block green space in front of the Milwaukee Road station on 4th St. Here is a list of Milwaukee’s large 19th-century recreational green spaces, all (except for Juneau Park) privately owned:

- 1849, Lueddemann’s-on-the-Lake. Gustavus Lueddemann was a farmer who bought land north of the fledgling city and built his farm on the bluffs where Lake Park is now. He early on recognized his property’s great views of the lake and welcomed city dwellers to picnic on his grounds, making money selling them food and beer. Christian Wahl and his parks commission bought Lueddemann’s property in 1890 for Olmstead’s planned Lake Park.

- 1850, Pius Dreher’s Milwaukee Garden, located between 14th and 15th St. and between State and Prairie (Highland). Dreher was a captain in the First Wisconsin Regiment during the Civil War. “His patronage is from the best ranks of our German population.” The Garden had band concerts and turner competitions.

- 1852, The Cold Spring Race Track, 27th and 35th St. between Juneau and Vliet. This massive area featured a horse track specializing in trotters and also served as a fairgrounds for several decades. It was subdivided in 1891 and McKinley Ave. was cut through.

- 1858, Miller’s Garden. Fred Miller bought a defunct brewery out on the west edge of town on 41st and State in 1855. Three years later he built a beer garden at the top of the hill overlooking the Menomonee Valley and his little brewery. His wife Lisette would serve food and beer and it became a favorite stop for travelers. There were bowling lanes and a three-story observation tower. It burned down in 1891 and was not rebuilt.

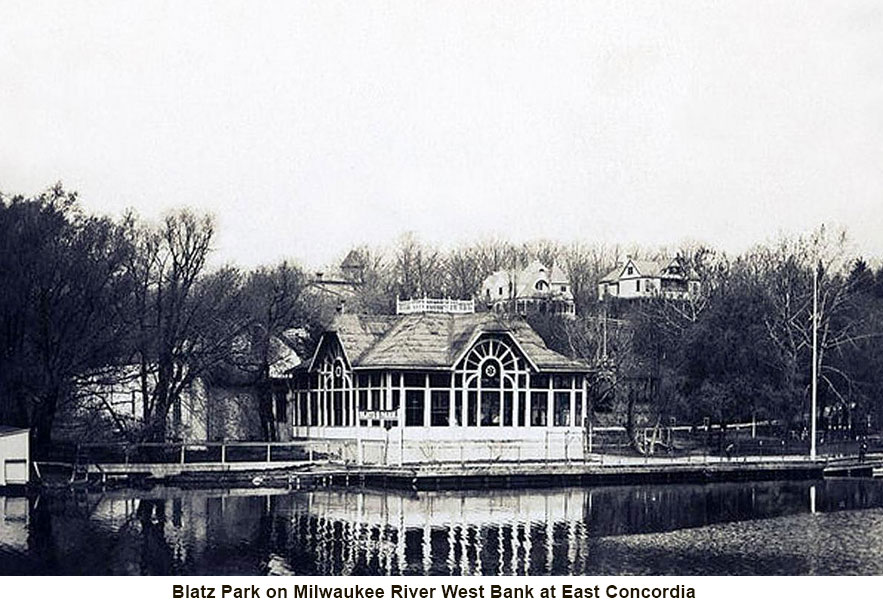

- 1870, Blatz Park, west bank of Milwaukee River at E. Concordia St. The large pavilion sat right on the river’s edge. Also called “Pleasant Valley Park,” this green space still exists and is a southern extension of Kern Park.

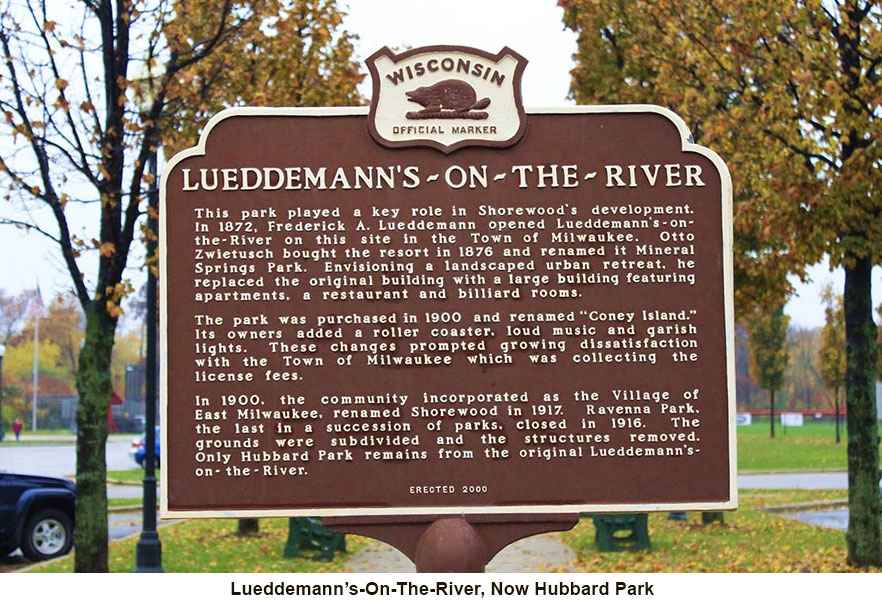

- 1872, Frederick Lueddemann’s-on-the-River (a son of Gustav Lueddemann?). Lueddemann bought a huge parcel of land along the east bank of the Milwaukee River in the unincorporated Town of Milwaukee, stretching from Edgewood Ave. all the way up to Capitol. Soda water magnate Otto Zwietusch bought it in 1876 and renamed it “Mineral Springs Park,” claiming to have discovered health-filled mineral spring water, which his company helpfully bottled and sold.

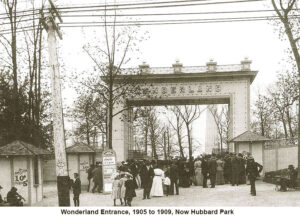

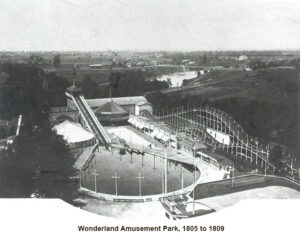

Taking advantage of the new Oakland streetcar line, new developers rebuilt the park into “Coney Island” in 1900 and built a roller coaster, water slide, and many other attractions. One very popular act was a woman who would stand on a tower, light herself on fire, and jump 40 feet into the river. The park was called “Wonderland” from 1905 to 1909 and “Ravenna” from 1909 to 1916. The local residents, however, grew tired of the lights and the large boisterous crowds and incorporated the town of East Milwaukee in 1900, renamed it Shorewood in 1917, and closed the amusement park down. Today’s Hubbard Park along the river is the last remnant. Ironically an extremely popular activity in recent summers is patronizing the beer garden there.

- 1870s, Berninger’s Park. The pavilion was on 31st and Pierce St. on the south

bluff overlooking the Menomonee Valley. The park closed in 1915. The building still stands.

- 1872, Shooting Park, later Pabst Park, Burleigh St. between 3rd and 5th Sts. The park was opened by the Milwaukee Schuetzengesellschaft. Frederick Pabst bought it in 1895 and sold a lot of beer there.

Its eight acres had a shooting range, beer garden, Katzenjammer palace fun house, Wild West shows, tiny railroad, and a roller coaster. There were band concerts every afternoon and evening in summer. The city bought it in 1921, renamed it Garfield Park and renamed it again as Clinton Rose Park.

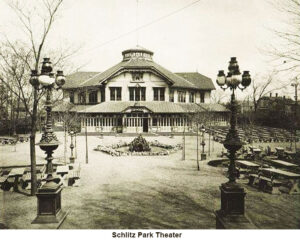

- 1879, Schlitz Park, Walnut St. north to Brown St., between 7th and 9th Sts. The Schlitz brewery developed a huge park just west of their brewery. It featured a small zoo, concert pavilion that could seat 5,000, restaurant, dance hall, tightrope walkers, and an enormous observation tower at the crest of a hill. It was a favored location for political rallies and speeches, as well as light opera productions. Roosevelt Middle School and part of Carver Park occupy the site today.

- 1881, Rose Hill Park, six acres between Forest Home Ave. and Muskego Ave. at 23rd St. It was developed by another German, William Miller, and had a parade ground, band stand, and dance hall. It could hold 15,000 people at a time. It was subdivided in the 1890s.

- 1883, National Park, 44 acres bounded by National Ave., Greenfield Ave., 31st St., and Layton Blvd. Its large track hosted horse races, as well as bicycle and motorcycle races. There were fox hunting and trapshooting in the woods, Milwaukee’s first roller coaster in 1885, hot-air balloon ascents, ice skating on the artificial lake in winter, and a field for early football games. It was the venue for the area’s annual Scottish Highland games. It closed in 1899.

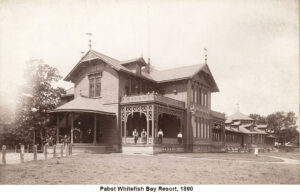

- 1889, Pabst Whitefish Bay Resort. This was the most elegant of them all. It was located on the bluffs above the lake at the foot of Henry Clay Ave. in what is now Whitefish Bay. Pabst built a large pavilion situated to enjoy the beautiful lake view; its restaurant featured planked whitefish. There were outdoor picnic tables, scenic paths that wound down the bluff to the lakefront, and Milwaukee’s first Ferris wheel.

Pabst arranged to have a streetcar spur, called the “dummy line,” built right up to the resort. Frederick Pabst himself was a former ship captain, and he chartered steamers, such as the Eagle and the Bloomer Girl, to pick up customers downtown at the Pabst dock on the river at Grand Ave. and haul them up to the resort pier. The resort closed in 1914.