The mention of the one-room schoolhouse calls to mind a picture of Laura Ingalls Wilder engaging a handful of students in rural South Dakota when she was only fifteen years old. Fans of the Little House books and television series may recall that she retired from her one-room school life at age eighteen to marry Almanzo and settle as a farmer’s wife.

Those old schoolhouses dotting the landscape of America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries told a tale of the grit and pragmatism of our forbearers. In 1919 there were 190,000 such schools and half the school-aged children in the United States attended one. The number dropped down to about 60,000 in 1950, then 20,000 in 1960. Now only 400 survive mainly in Montana and Nebraska.

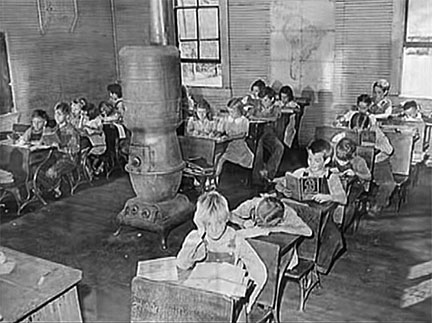

The earliest schools were most often log cabins with benches and plank desks. Later came the familiar white clapboard construction, a reflection of the small rural church which often administered them. Local farmers and craftsmen contributed to the construction and followed common architectural tradition. The dominant features inside were the open areas in the front with the teacher’s desk and chalkboard and the pot belly stove in the center. The windows ran along the side as in the town church, and many had steeples with bells atop the roof.

In those quaint settings, a lone teacher presided over the basics of reading first and then moved on to writing and arithmetic. Students of all levels would study together, often the older assisting the younger, though it could go the other way as well. It was the three Rs and maybe the globe on the teacher’s desk—science and social studies were typically only offered in the larger schools. Gritty and lonely and somewhat cold, yet beautiful in its austere efficiency—one imagines Jim Burden working dreamily away In My Ántonia.

Schoolteachers had responsibilities beyond teaching. Some did the work of a janitor to keep the place clean. That could mean hauling water and firewood if no strong boys were around. It certainly meant umpiring games, tending to skinned knees, and managing parent relations.

In the early days, the teachers were indeed often very young like Laura Ingalls Wilder as training was marginal. School boards often hired for gender, a male teacher for the older students and a female for younger, or a male for mostly male students or perhaps in the winter session in states like Nebraska and Wisconsin, and a female for spring when the men went back to work the farm. These were pragmatic decisions. During the Civil War teachers became predominantly female.

Formal teacher training began with certificate programs in the late nineteenth century, some programs run via correspondence, others through the local high school. Teachers’ colleges came late in the century. The Normal School in Cedar Falls, Iowa, opened in 1876 and began to prepare teachers for every district in the state through three, six, or twelve-week training classes. Then in 1909 the Normal School became the Iowa State Teachers College and ramped up credit hour requirements to keep pace with ongoing reforms.

The earliest schools, those reaching back to the seventeenth and early eighteenth century had focused on literacy for the purpose of doctrinal and moral instruction. However, the lack of homogeneity in American religion suggested that the best way to organize all the schools in a geographic area was through parent groups called School Societies. These were eventually dissolved in the 1830s in favor of School Districts supported by tuition. Then in the early 1900s this gave way to Boards of Education for the monitoring and support of district schools.

Students could continue their studies until they or their parents concluded enough had been learned. High school attendance was not typical especially in farming communities until into the 1900s.

Compulsory education laws were not enacted in many states until into the 20th century. Virginia passed such a law in 1908, Mississippi in 1918. Still by 1900, enrollment in elementary schools was effectively 100 percent even where compulsory education laws had not been passed.

Enrollment in secondary schools came much slower than elementary. At the turn of the 20th century enrollment for 14 to 17-year-olds was at about 75 percent. It experienced a gradual percentage increase to 90 in 1950, and 95 percent nationwide by the late 90s.

The school year varied in the early days. A community with a larger economy might have a 41-week school year, while a farm community might only offer 30 weeks, the children needed to assist at home. In 1869 the national average was 132 days. The current 180-day school year became law in most states around 1880.

The school day typically extended from 9:15 to 4:30 but with two recesses and an hour and a half lunch, allowing students to walk home and back. The schools were built within walking distance to the main houses in the community or to the centers of the local economy, like cheese factories in Wisconsin.

A footnote to all this is that the one-room schoolhouse produced the likes of Jefferson and Lincoln and Henry Ford, while our current public educational system has not fared well. Those one-room schools allowed individualized instruction and consistent discipline, the characteristics celebrated by today’s advocates of school vouchers, charter schools and homeschools. They were sources of civic pride and community value. Where they still exist, they remain unique centers of learning, and reminders of how America came to be.