In 2014 residents of Webster City, Iowa, rallied to save their local movie house, The Webster on the 2nd Street strip was sandwiched between the Hallmark shop and Bettis Appliance and Television. Residents might watch Five Feet Apart this weekend for $4.

After a manufacturing plant closed in Webster City in 2013, the citizenry gathered together and decided the best way to begin pulling out of the malaise was to raise $200,000 for the restoration of their beloved Webster. The town boasts a population of about 8000, and they were not going under.

What happened in Webster City is being repeated in other communities around the country where locals have woken up to the importance of an historic movie house.

Take Coos Bay, Oregon, population 16,680 where the city council got involved and led a fundraising campaign that raised over a million dollars for the complete restoration and reopening of the historic Egyptian Theater. The Egyptian now caters more to a specialty audience of film buffs and art lovers, but it is always busy.

Similar has occurred in Amery, Wisconsin, population 2902, where a 2013 restoration brought back the art deco masterpiece Amery Theater; and in Franklin, Indiana, population, 23,712, where the old Artcraft Theater originally opened in 1922 has been completely restored; and in Manistee, Michigan, population 6226, where the Vogue Theater underwent a 2.5 million dollar transformation.

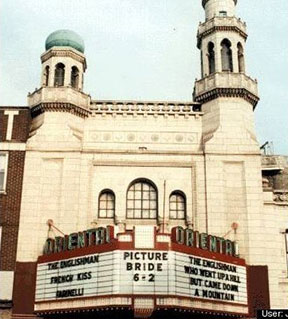

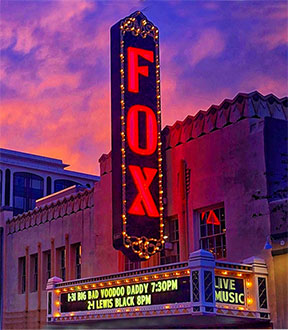

The trend parallels one targeting key neighborhood theaters in mid to large cities, as with the restored Commodore Theater in Portsmouth, VA, or the Oriental in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, or the Fox in Tucson. Behind the trend, a grassroots understanding is emerging: vibrant local movie houses translate into vibrant local communities.

Many readers will recall the impact of the close of some local treasure in their community in the early to mid-sixties—the decade when the tide seemed to turn. PJ Danielson of Chicago recounts seeing a sign in the box office window of the Admiral Theater in his blue collar Albany Park neighborhood saying only eight folks had shown up the previous Friday to see the featured Oliver. That led to the theater changing hands and reopening in 1971 as a venue for the newly legal blue films. Needless to say, the decline of the Admiral marked a low-water mark for the community. The blue owner, “Patsy” Ricciardi, was eventually found in the trunk of a parked car, his body riddled with bullets.

Between the two World Wars, Americans had fallen in love with movies, the major studios each putting out an average of a film a week. That meant plenty of product to distribute to theaters all across the country. As the studios also owned about 17% of the theaters, the business had a guaranteed market lucrative for all.

Things began to change when the Hollywood Antitrust Case of 1948 divested the studios of control of the theaters; this resulted in two crippling adjustments that worked against the smaller markets. First, it opened the door to greater competition for first-run films and the eventual boom of the larger suburban multiplexes. Then also it lengthened the time period between first release of a film and the secondary release to the small markets.

Major studios had employed regional sales branches throughout the heyday of the big studios to ensure good distribution. When tighter margins forced consolidation of these branches, the result was often a pink slip for the members of the sales team who knew the small theaters best. Local theaters could still get a new release, but not as soon as before, and then when the film finally arrived, changing corporate policy required the theater show the film for three weekends at least. It was those third weekends when the whole town had seen the feature and the audience would barely break a dozen that crippled the local owners.

The decline of the 60s and 70s spelled the end of more than the convenience of a movie theater within walking distance. It ended the era of the accessible, wonderful, albeit gaudy opulence of the old movie houses, the easy date venues, the safe place for the kids on weekends. In towns across America mythologized as Mayberry RFD, a few hours at the movies was a staple of the week’s natural rhythm. Change now meant getting in the car and driving away, not only from the local theater, but also from the local restaurants, bowling alleys, taverns, and sweet shops.

A night or afternoon at the movies had come to mean more than just the latest Tracy and Hepburn comedy, which might be good or bad, or one good coupled with one bad, the first show of the double-feature. It meant fulfilling a familiar local ritual. More than the movie, the neighborhood movie house was about the smell of the popcorn and the stiff look of the uniformed ushers and the red velvet curtain opening before the screen. It was about dish-night giveaways, cry rooms for children, signs that told women and men to remove their hats, and ashtrays built into the arm rests—cozy reminders that the movies supported traditional American family life. They knit communities into a common, but far less mass culture.

When you sat back in those local palaces, you didn’t melt into a single overly long feature as you do now, preceded by an interminable stream of trailers. You got your news at the theater, black and white newsreels accompanied by authoritative voiceovers keeping you up on the war effort or stories of national interest. Your kids got a cartoon, a good one, too, like the original Bugs Bunny or Roadrunner or Woody Woodpecker or Popeye or a classic from Max Fleisher like Betty Boop—cartoons that adults could enjoy. At the weekend matinees, the kids could gather material for playground conversation regarding Crash Corrigan battling Unga Khan and the Black Robe Army or the latest cliffhanging exploits of The Spider or The Shadow or Beatty in Africa.

Those older theater days cannot be reproduced in modern America, but it is good to see communities awakening to the value of what those days represented. And theater business is still viable despite recent laments. In 2018, attendance surprisingly rose 8%. According to Jeff Logan who owns The Dells in Dell Rapids, South Dakota, population 3633, “movie-going still has a solid future in smaller towns as it provides a cost-effective, out-of-home experience.” Experience is the key word.