In 1998 a staffer at Beloit College in south-central Wisconsin forwarded a list of relevant facts to orient colleagues to the culture of incoming students; that is, what new students, mostly born in 1980, would know and not know.

On that original Mindset List were items like, your new students “never had a polio shot, and likely, do not know what it is.” And, “The expression ‘you sound like a broken record’ means nothing to them.”

The Beloit list went viral and has been updated every year since its inception to the chagrin of an older generation dazed by the rapid changes of the modern world. We might well conclude from the popularity of the list that the pace of cultural change poses an existential threat to everyone over twenty-something, which is the bulk of us.

Recently I heard an interview with the philosopher Alice Von Hildebrand, a youthful 96 at the time of this writing, who commented in passing that her father-in-law had been born in the 1840s. The interviewer was rendered speechless. The 1840s suggested antiquity to him, a world beyond imagination.

C.S. Lewis dubbed this attitude “chronological snobbery,” the modern assumption that the thinking, art, and science of previous ages was inherently inferior to that of our own. We see this snobbery played out most vividly in the stereotypical “millennial” who will ground all arguments in the assumption that individual opinions are of equal merit and that authority of any kind is not to be trusted.

One hopes that young lemmings will eventually be oriented better by the harsh realities of survival in the adult world. Yet, we ought to sympathize, nonetheless, with their perception that something has profoundly challenged participation in a larger and older cultural tradition.

How can we preserve the best of the past? Time and change have so accelerated that the immediate concern for the individual is taking hold of the subway strap before collapsing into the person standing nearby.

Just how much has the culture changed? Well, forget the generational Mindset List and consider life a hundred years ago. Here are a few interesting statistics from the year 1918:

- The average life expectancy for men was 47 years.

- Only 8 percent of homes had a telephone.

- More than 95 percent of all births took place at home.

- The third leading cause of death was diarrhea after pneumonia and tuberculosis.

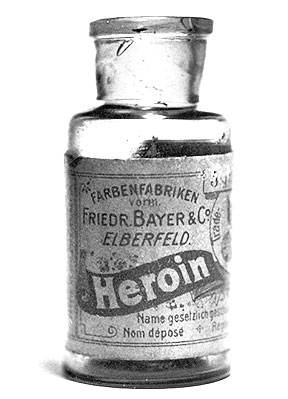

- Heroin was available over the counter as a cure for a variety of common maladies.

- Only 230 murders were recorded in the entire United States.

Note that in 1918 Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, T.S. Eliot and other literary luminaries were dubbed a “lost generation” seeking asylum in Paris from a modern America that rendered life for them “disoriented, wandering, directionless.”

That “modern” was a far cry from our new modern. Mortality in 1918 modern was an immediate concern, particularly for men, and not because of processed food and theories about climate change.

Communication between family members was slow and, therefore, more to be valued.

The home was where most people were born and where they died and were laid out after they died. And so, the home meant something defined and nearly sacred.

The medical profession was not considered the last great hope for mankind, and certainly not that for which a person should spend a lifetime saving to support.

And, of course, your daughter could leave the house in the morning on her bicycle without you feeling the need to monitor her safety at each marker along the way.

Boil it all down—it seems reasonable to generalize that the new modern reality we face is less sober, less careful, less family-oriented, and far less self-reliant.

On the positive side, we live longer and have many more ways to talk about our existential crises.

But perhaps you noticed this already.