Long before Polaroid made it possible to capture that special moment and wait expectantly through the development process, Americans enjoyed the tintype. The tintype allowed many a young girl to preserve her sunny afternoon likeness on a small plate that a poor young soldier might clutch on a muddy battlefield. Many an immigrant patriarch posed with his family in his Sunday best proud to show that the long journey over ocean and across the plain had indeed resulted in a better life in the new land.

Tintypes were an evolution of the ambrotype, an early photographic process capturing a positive image on a glass plate through the wet collodion process. Ambrotypes were less expensive than the earlier daguerreotypes which produced images on copper plates, and the tintype process was cheaper still in that the image was imprinted on a sheet of lacquered iron.

Tintypes made photographs convenient. Ordinary people could carry with them the image of a loved ones on a plate that required no protective case. And it was a quick process for that summer afternoon—the tintype could be made coated, shot, and developed in less than six minutes.

The tintype process had its hazards, however, due to the toxic chemicals required, and many entrepreneurial early photographers who hawked their tintype services across the United States and Canada died young. Those casualties were not seen by the buyers, of course, who only saw the possibility of memory preservation previously unimagined.

The photographer would start by purchasing the pre-made plates, thin sheets of iron with a brown or black lacquer coating. The photographer would then coat that with collodion containing bromides or iodide and immerse it in a silver nitrate sensitizer bath. Once the plate was exposed in the camera, it would be developed with a solution of ferrous sulfate and nitric acid and fixed in a sodium thiosulfate or potassium cyanide bath. After drying, the image was finished with a protective varnish. The process produced a finished negative with subjects reversed as in a mirror.

The tintype industry was popular well into the twentieth century as it allowed photographers to produce portraits on street corners or at fairs or around sites of battles, a practice popular during the Civil War. The flood of immigrants westward in the States and Canada provided an early market for itinerant photographers who would travel in horse-drawn

wagons, developing photos in the back to create these priceless mementos. Other tintypists would set-up shop in front of beaches, fairs, and parks. They were the street photographers of their day—capturing and preserving memories. Tintypes were eventually replaced in the 1920s when roll-film cameras began to circulate and offer a better solution to the need for the quick picture.

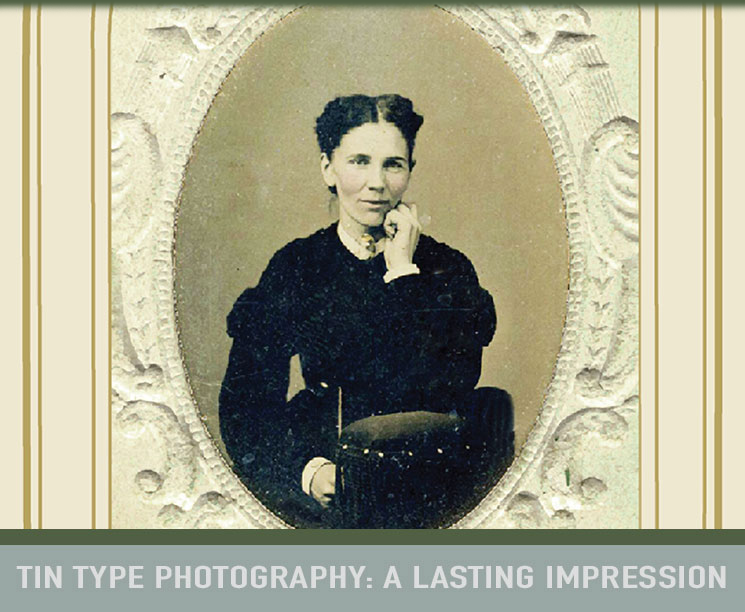

The earliest tintypes featured subjects in full length, the men often with fedora and walking stick, and the women in full dress. Little special notice was given to the face, and backgrounds were kept simple. Posing was the high end of the art form. The typical plate was small, approximately 2.5 by 4.5 inches, and many tintypes were as small as postage stamps.

The tintype method can be traced to 1853 when French photographer and scientist, Adolphe-Alexandre Martin, developed the technique and published his methods for the French Academy of Science. His reports did not catch on with the French who had full investment in the daguerreotype process, but two Americans, William and Peter Neff, eventually purchased the patent rights for the plating process and opened a gallery in Cincinnati in the spring of 1856. By 1857, continued experimentation refined the process to improve resistance and better the color hues.

Tintypes are still created by photographic artists in our own day who find attractive their suggestion of historical time. Originally, however, they simply gave common people the ability to express themselves and so share their love, personality, or status.

The world of photography took a step forward when the tintype was developed. Photos became accessible, affordable, and fun—keepsakes that any ordinary person with modest means could cherish.